x = 100

type(x)<class 'int'>This section provides a brief introduction to programming in Python, covering the basics of the language, essential libraries for data analysis, and best practices for coding. The goal is to equip you with the skills needed to work with Python effectively in the context of artificial intelligence and big data.

Python has become the de facto standard for AI and data science due to its simplicity, readability, and rich ecosystem of specialized libraries. Throughout the course, we will use Python for various tasks, including data manipulation, visualization, statistical analysis, and implementing machine learning algorithms. By the end of this section, you should be comfortable with Python’s core concepts and ready to tackle basic real-world AI challenges.

Note that programming is a skill that cannot be mastered overnight. It requires practice and continuous learning. I encourage you to experiment with the code examples provided in this section and to work through the exercises. Don’t worry if things don’t click immediately; programming fluency develops through repetition and problem-solving.

The material in this section draws from the material developed by Alba Miñano-Mañero and extended by Jesús Villota Miranda, which they kindly prepared for another data science course that I taught at CEMFI.

Python is a high-level, interpreted programming language created by Guido van Rossum and first released in 1991. It emphasizes code readability and simplicity through its clean syntax and use of significant whitespace, making it an ideal language for both beginners and experienced programmers. Python is a general-purpose language that excels across diverse domains—from automation to scientific computing and artificial intelligence. Its extensive standard library and vast ecosystem of third-party packages enable rapid development and prototyping. Today, Python is one of the most popular programming languages worldwide and has become the lingua franca of data science and machine learning, largely due to powerful libraries like NumPy, Pandas, scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and PyTorch.

While languages like R, Julia, and MATLAB, or sometimes even lower-level languages like C++ are used in data science and AI, Python offers distinct advantages for this course:

That said, other languages have their strengths: R, for example, excels in statistical analysis and visualization and Julia offers superior performance for numerical computing. Python strikes the best balance for our purposes: accessible enough for newcomers yet powerful enough for production systems.

For this course, we will primarily use Nuvolos, a cloud-based platform that provides a pre-configured Python environment with all necessary libraries and a VS Code interface. This eliminates installation headaches and ensures everyone has an identical setup. You can access Nuvolos through the link in the sidebar.

However, learning to set up Python locally is a valuable skill for future projects. If you wish to work on your own machine, here are the general steps to install Python and the required packages:

Install Python via Anaconda/Miniconda: Anaconda is a distribution that bundles Python with common data science packages. Miniconda is a lighter version that installs only Python and the conda package manager, allowing you to install packages as needed.

Create a virtual environment: Virtual environments isolate project dependencies, preventing version conflicts between projects. Use conda env create -f https://ai-bigdata.joelmarbet.com/environment.yml to create the environment required for this course.

Install additional packages: If required, you can install additional packages individually (e.g., conda install numpy).

Set up VSCode: Install Visual Studio Code and add the Python and Jupyter extensions. VSCode provides an excellent development experience with features like code completion, debugging, and integrated notebook support.

Detailed installation instructions on how to install the environment used in this course are available in the “Notes for Local Installation” PDF linked in the sidebar. For troubleshooting or platform-specific issues, consult the documentation or reach out after class or by email.

A good development environment significantly improves your productivity and learning experience. This section covers the main tools you’ll encounter in this course.

VSCode is a free, lightweight, yet powerful code editor that has become a developer favorite for many different programming languages. It combines the simplicity of a text editor with features traditionally found in full IDEs.

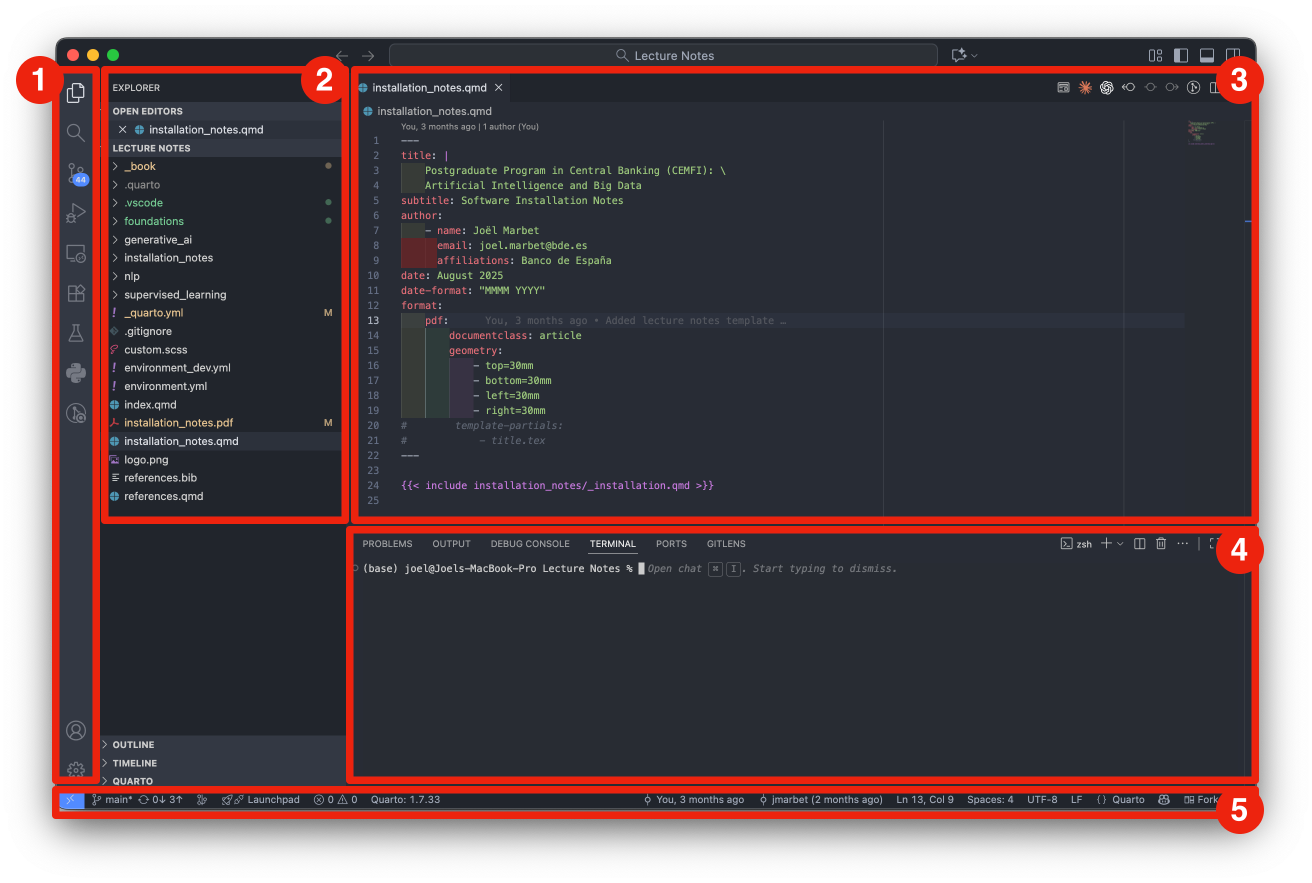

Figure 2.1 shows the main components of the VSCode interface:

Note that not all elements are always visible; for example, the Panel is hidden by default and can be toggled as needed.

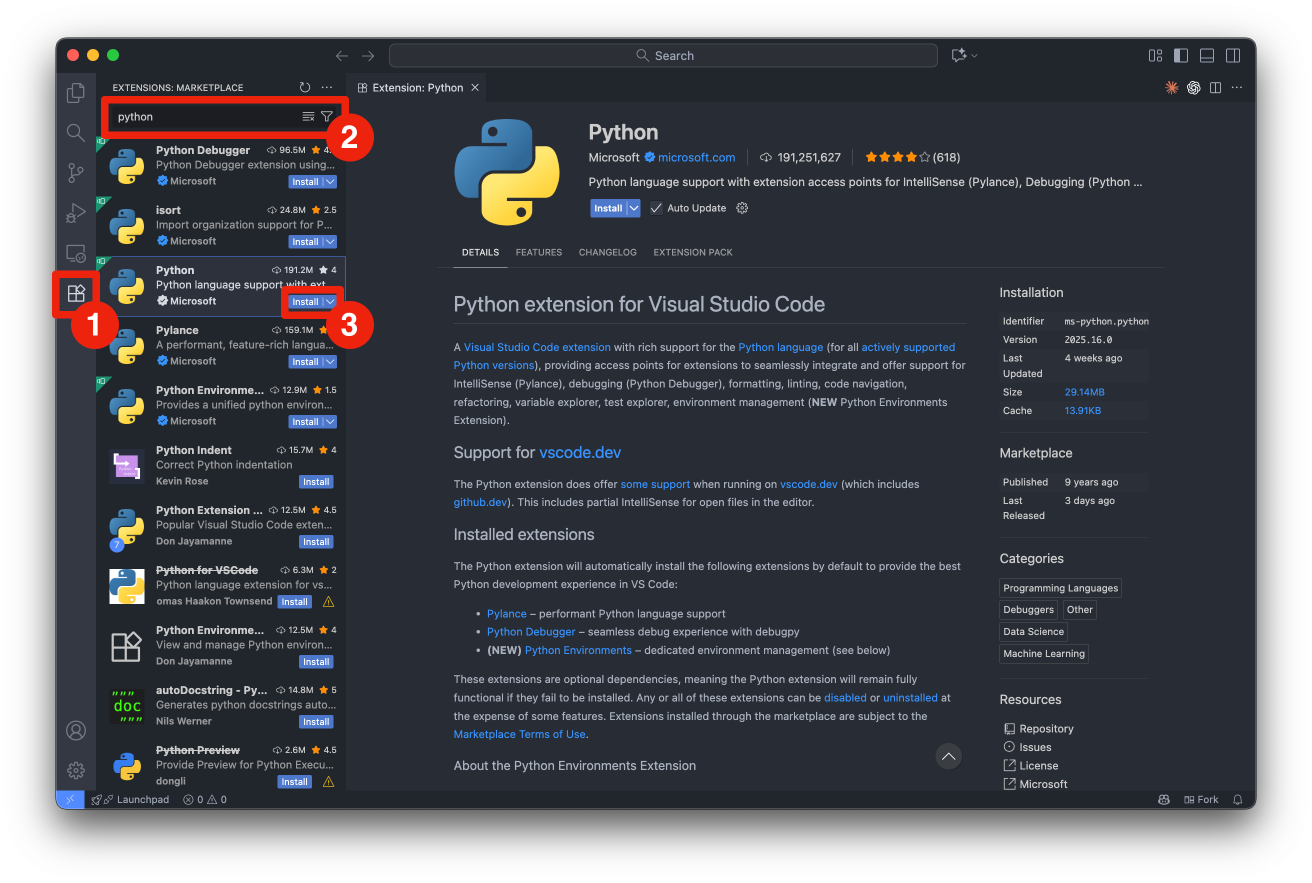

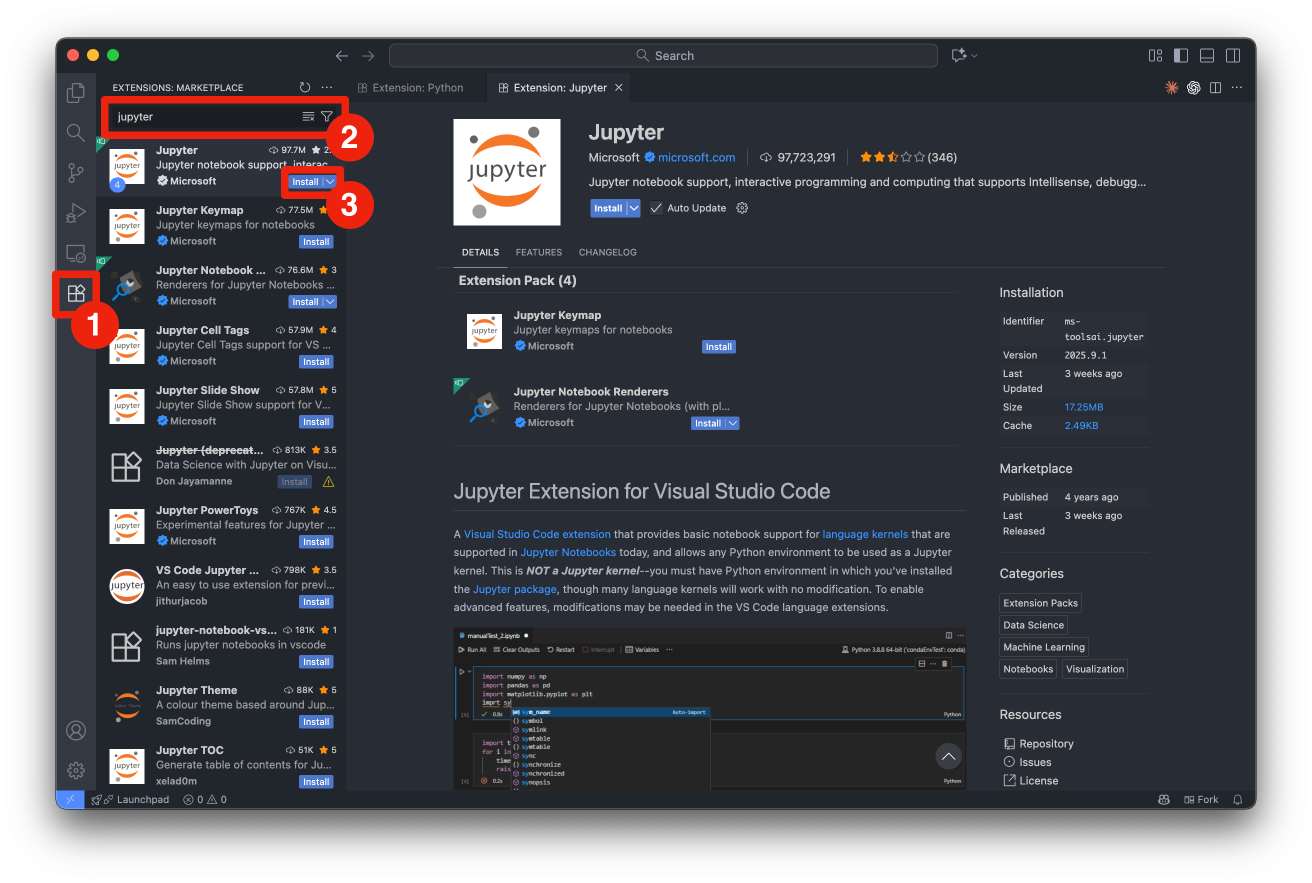

For Python development, you’ll want to install the following extensions in VSCode:

You can install extensions by clicking on the Extensions icon in the left sidebar and searching for them by name.

We will primarily use VSCode within Nuvolos for this course, but you can also set it up locally following the installation instructions provided earlier. Note that the version on Nuvolos has an additional menu button at the top left, which provides access to menus to open files, settings, and other options. In the local version of VSCode, these options are available in the standard menu bar at the top of the window/screen.

The main way we will interact with Python code in this course is through Jupyter Notebooks. Jupyter Notebooks, as well as the popular Jupyter Lab, are all part of the Jupyter Project which revolves around the provision of tools and standards for interactive computing across different computing languages (Julia, Python, R).

Jupyter Notebooks are interactive documents that combine live code, visualizations, and explanatory text. They’re ideal for exploratory data analysis and prototyping. They allow you to write and execute code in small chunks (cells), see immediate outputs, and document your thought process alongside the code. While Jupyter Notebooks are excellent for exploration and learning, they may not be the best choice for production code or large projects due to challenges with version control and code organization. However, they remain a popular tool in data science and AI for their interactivity and ease of use. We will execute Jupyter Notebooks within VSCode instead of the more traditional browser-based interface. The reason for this choice is to provide a unified development environment where you can seamlessly switch between writing notebooks and scripts, debugging code, and managing files. Furthermore, VSCode integrates well with recent AI-assisted coding tools, which can enhance your productivity.

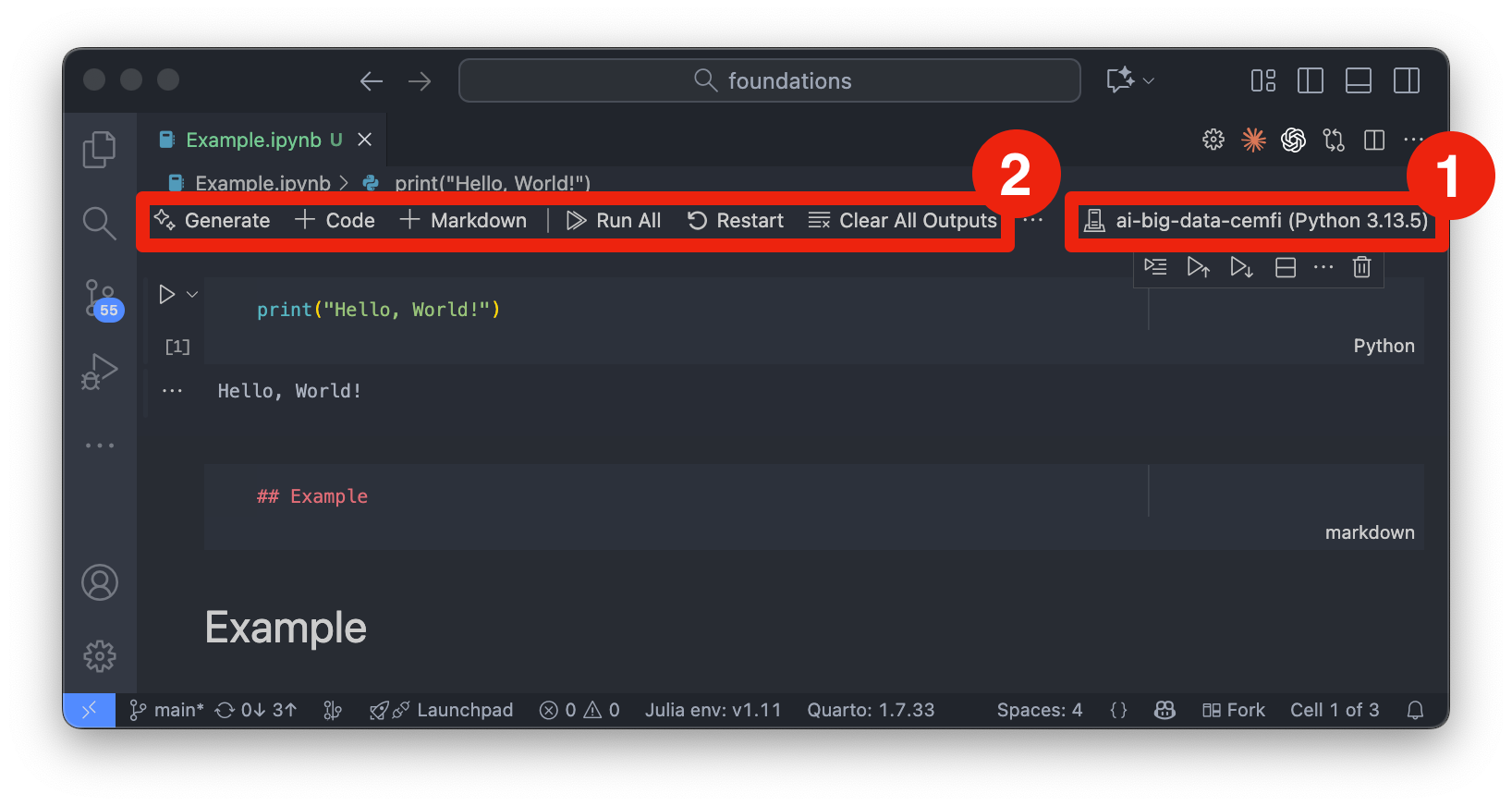

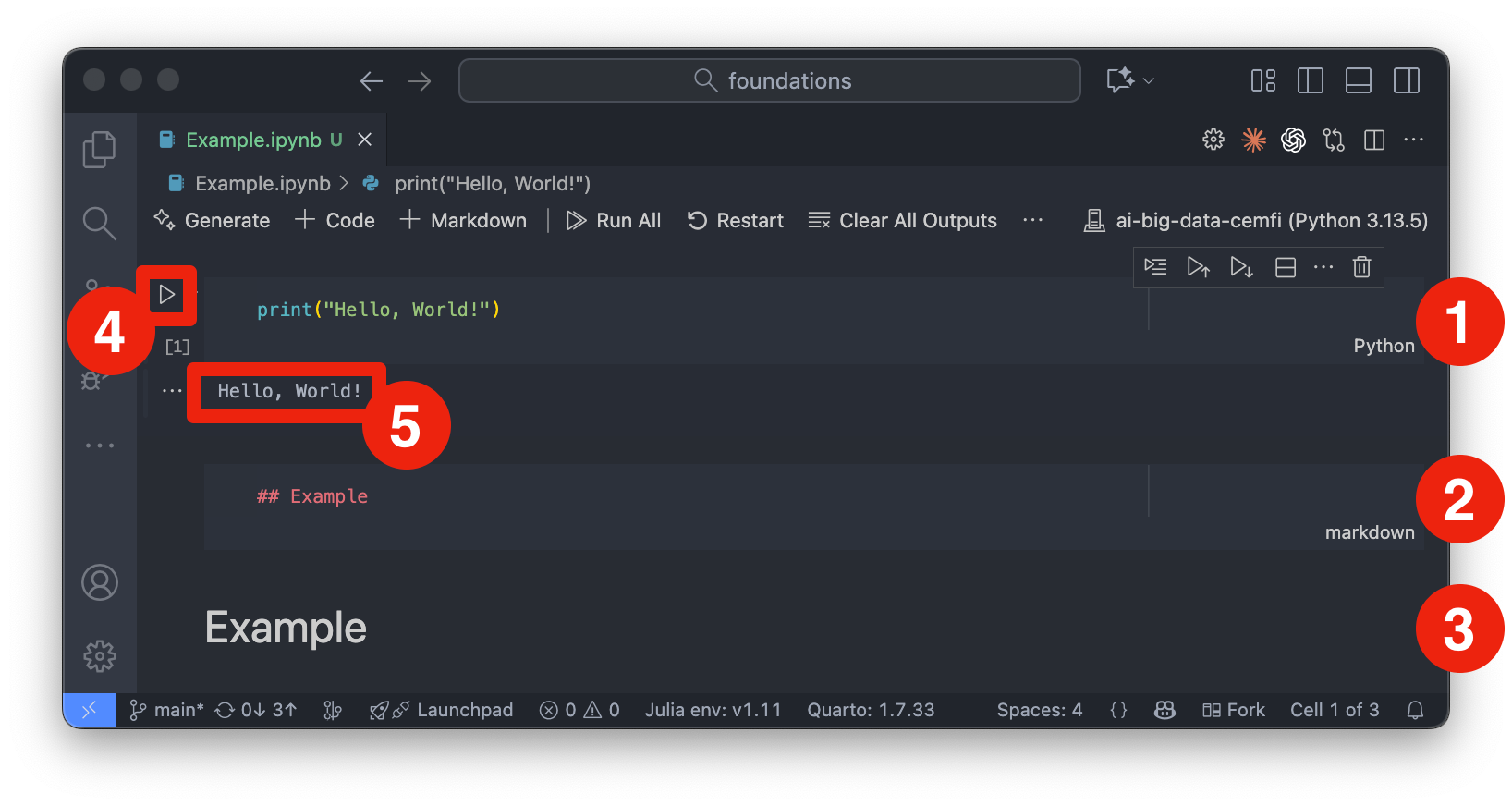

Figure 2.2 shows an example of a Jupyter notebook opened in VSCode. To work with Jupyter notebooks in VSCode, follow these steps:

.ipynb) or create a new one from the menu (“File” -> “New File” and then select “Jupyter Notebook”).ai-big-data-cemfi as the kernel. You can change the kernel by clicking on the current kernel name (or “Select Kernel”) in the top-right corner of the notebook interface (denoted by number 1 in Figure 2.2). Then, click on “Python Environments” and select ai-big-data-cemfi from the list.If you have done this correctly, you should see ai-big-data-cemfi displayed as the selected kernel as shown in Figure 2.2.

A Jupyter notebook consists of a sequence of cells, which can be of two main types:

These cells can be created from the toolbar at the top of the notebook interface (denoted by number 2 in Figure 2.2) or from the + button appearing under cells when hovering over them. From the toolbar you can also run cells, stop execution, restart the kernel, and perform other notebook-related actions. Cells can also be executed by selecting them and pressing Shift-Enter or by clicking the “Play” button in the toolbar (denoted by number 4 in Figure 2.3). Once you run a cell, the output will appear directly below it (denoted by number 5 in Figure 2.3). Markdown cells can be edited by double-clicking on them, and you can switch between code and markdown cell types using the dropdown menu in the toolbar. Number 2 and 3 in Figure 2.3 show markdown cells that are being edited and rendered, respectively. Number 1 in Figure 2.3 shows a code cell. Note that code cells have “Python” written in the bottom right corner to indicate the language being used.

Another way to write and run Python code is through scripts. Scripts are plain text files with a .py extension that contain Python code. They are executed as a whole, either from the command line or within an IDE like VSCode. They are better suited for larger projects, production code, and automation tasks.

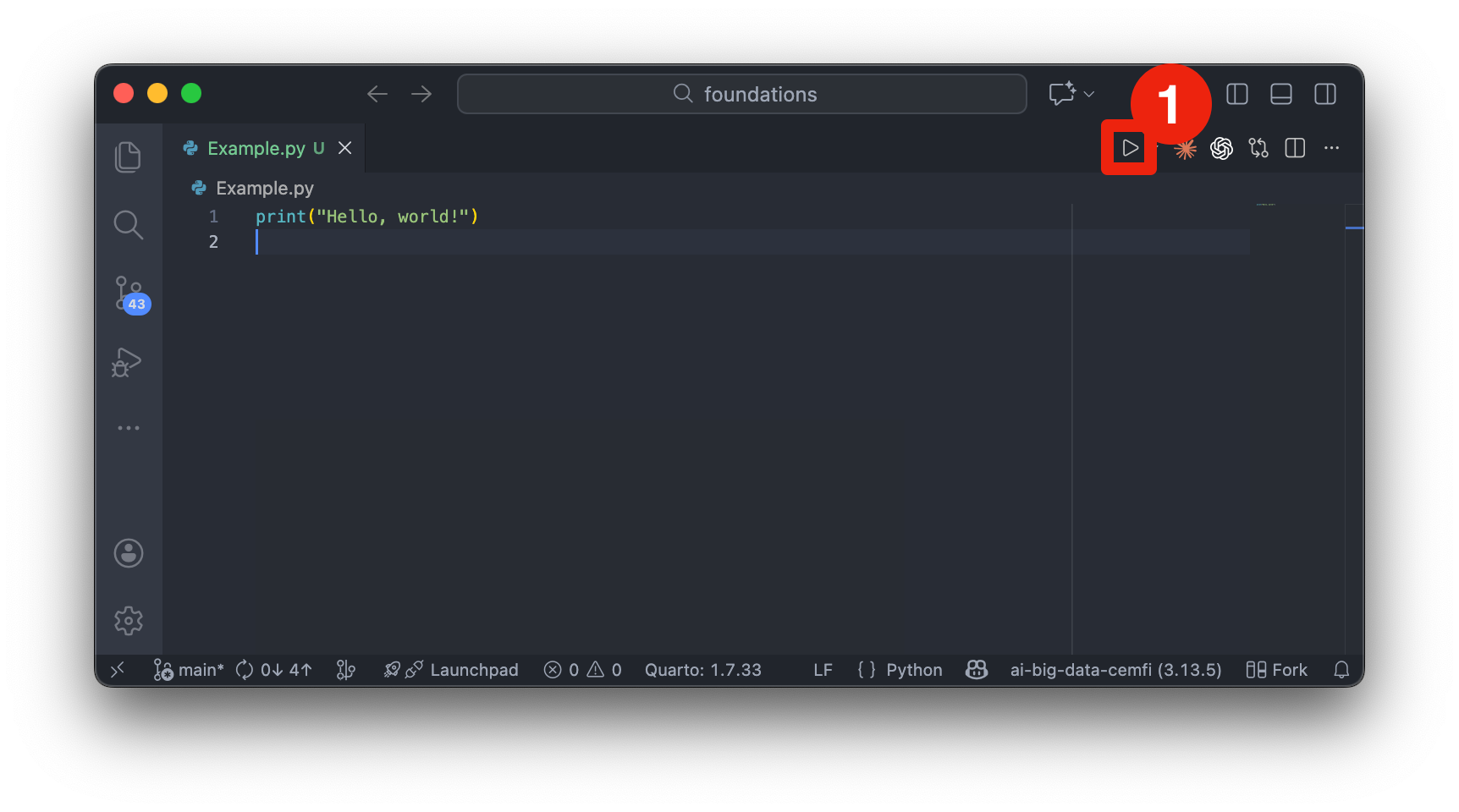

Figure 2.4 shows an example of a Python script opened in VSCode. You can run the entire script by right-clicking anywhere in the editor and selecting “Run Python File in Terminal” or by clicking the “Play” button (denoted by number 1 in Figure 2.4). The output will appear in the integrated terminal at the bottom of the VSCode window.

When to use notebooks:

When to use scripts:

Best Practices:

We will primarily use Jupyter notebooks for in-class exercises and exploratory tasks, but I will provide some Python scripts as examples. Understanding both formats is important for effective Python programming.

Google Colab is a free cloud-based Jupyter notebook environment that requires no setup and provides free access to GPUs. It’s particularly useful for:

Limitations:

If you have trouble installing the environments locally, Google Colab can be a good alternative. To use Colab, simply navigate to colab.research.google.com. There you can create a new notebook or upload an existing one. I will provide links to the notebooks used in this course that you can open directly in Colab if needed. However, Nuvolos is the preferred environment for this course and will give you the best experience.

Python is an interpreted language. By this we mean that the Python interpreter will run a program by executing the source code line-by-line without the need for compilation into machine code beforehand. Furthermore, Python is an Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) language. Everything we define in our code exists within the interpreter as a Python object, meaning it has associated attributes (data) and methods (functions that operate on that data). We will see these concepts in more detail later.

First, let’s have a look at the basics of any programming language. All programs consist of the following

Variables are basic elements of any programming language. They

Python is dynamically typed, meaning you don’t need to declare variable types explicitly. The interpreter infers the type based on the assigned value. For example, the following code creates a variable x and assigns it the integer value 100. The type() function is then used to check the type of the variable.

x = 100

type(x)<class 'int'>The Python interpreter output int, indicating that x is of type integer.

As the example above shows, you can create a variable by simply assigning a value to it using the equals sign (=). What happens under the hood is that Python creates an object in memory to store the value 100 and then creates a reference (the variable name x) that points to that object. When you later use the variable x in your code, Python retrieves the value from the memory location that x references. For example, we can then do computations with x:

y = x + 50

print(y)150Python retrieved the value of x (which is 100), added 50 to it, and assigned the result to the new variable y.

Note that you can reassign variables to new values or even different types. For example, you can change the value of x simply by assigning a new value to it

x = 200

print(x)200Note that now x points to a new object in memory with the value 200. The previous object with the value 100 will be automatically cleaned up by Python’s garbage collector if there are no other references to it. This might not seem important now, but there are some implications of this behavior when working with mutable objects, which we will cover later.

The process of naming variables is an important aspect of programming. Good variable names enhance code readability and maintainability, making it easier for others (and yourself) to understand the purpose of each variable.

For example, consider the following two variable names

a = 25

number_of_students = 25The first variable name, a, is vague and does not convey any information about what it represents. In contrast, number_of_students is descriptive and clearly indicates that the variable holds the count of students. This makes the code more understandable, especially in larger programs where many variables are used.

Python imposes certain rules on how variable names can be constructed:

if, else, while, for, etc.). help(keywords) will show which words are reserved.Variable, variable, and VARIABLE would be considered different variables.In addition to these rules, good practices for naming variables include to

snake_case) for better readability (some programmers use camelCase, but snake_case is preferred in Python)type we will no longer be able to use type to access the type of variables)The following code snippet lists all reserved keywords in Python that cannot be used as variable names

import keyword

for kw in keyword.kwlist:

print(kw)False

None

True

and

as

assert

async

await

break

class

continue

def

del

elif

else

except

finally

for

from

global

if

import

in

is

lambda

nonlocal

not

or

pass

raise

return

try

while

with

yieldMake sure you don’t use any of these words as variable names in your code.

Python has several built-in data types that are commonly used:

int): Whole numbers, e.g., 42, -7float): Numbers with decimal points, e.g., 3.14, -0.001complex): Numbers with real and imaginary parts, e.g., 2 + 3jstr): Sequences of characters enclosed in single or double quotes, e.g., 'Hello, World!', "Python"bool): Logical values representing True or FalseSince Python is dynamically typed, the creation of variables of these types is straightforward, as shown in the following examples:

this_is_int = 5

type(this_is_int)<class 'int'>this_is_float = 3.14

type(this_is_float)<class 'float'>this_is_complex = 2 + 3j

type(this_is_complex)<class 'complex'>this_is_str = "Hello, Python!"

type(this_is_str)<class 'str'>this_is_bool = True

type(this_is_bool)<class 'bool'>Note that boolean values are special in the sense that they are equivalent to integers: True is equivalent to 1 and False is equivalent to 0. This means you can perform arithmetic operations with boolean values, and they will behave like integers in those contexts.

There is another data type called NoneType, which you might encounter. It represents the absence of a value and is created using the None keyword.

this_is_none = None

type(this_is_none)<class 'NoneType'>You can also create more complex data types, which we will cover in the section on data structures.

A key element of programming is manipulating the variables you create. Python supports various basic operations for different data types, including arithmetic operations for numbers, string operations for text, and boolean operations for logical values.

Arithmetic Operations: You can perform arithmetic operations on integers and floats using operators like +, -, *, /, // (floor division), % (modulus), and ** (exponentiation).

a = 10

b = 3sum_result = a + b # Addition

print(sum_result)13diff_result = a - b # Subtraction

print(diff_result)7prod_result = a * b # Multiplication

print(prod_result)30div_result = a / b # Division

print(div_result)3.3333333333333335floor_div_result = a // b # Floor Division

print(floor_div_result)3mod_result = a % b # Modulus

print(mod_result)1exp_result = a ** b # Exponentiation

print(exp_result)1000String Operations: Strings can be concatenated using the + operator and repeated using the * operator.

str1 = "Hello, "

str2 = "World!"

concat_str = str1 + str2 # Concatenation

print(concat_str)Hello, World!Sometimes, you may want to repeat a string multiple times

repeat_str = str1 * 3 # Repetition

print(repeat_str)Hello, Hello, Hello, Another useful operation is string interpolation, which allows you to embed variables within strings. This can be done using f-strings (formatted string literals) by prefixing the string with f and including expressions inside curly braces {}.

name = "Alba"

age = 30

intro_str = f"Her name is {name} and she is {age} years old."

print(intro_str)Her name is Alba and she is 30 years old.Boolean Operations: You can use logical operators like and, or, and not to combine or negate boolean values.

bool1 = True

bool2 = False

and_result = bool1 and bool2 # Logical AND

print(and_result)Falseor_result = bool1 or bool2 # Logical OR

print(or_result)Truenot_result = not bool1 # Logical NOT

print(not_result)FalseTo compare values, you can use comparison operators like == (equal to), != (not equal to), < (less than), > (greater than), <= (less than or equal to), and >= (greater than or equal to).

a = 10

b = 20eq_result = (a == b) # Equal to

print(eq_result)Falseneq_result = (a != b) # Not equal to

print(neq_result)Truelt_result = (a < b) # Less than

print(lt_result)Truegt_result = (a > b) # Greater than

print(gt_result)Falsele_result = (a <= b) # Less than or equal to

print(le_result)Truege_result = (a >= b) # Greater than or equal to

print(ge_result)FalseNote that the result of comparison operations is always a boolean value (True or False). This will be useful when we discuss conditional statements later.

Be careful not to confuse the assignment operator = with the equality comparison operator ==. The single equals sign = assigns a value to a variable, while the double equals sign == checks if two values are equal and returns a boolean result.

We can also combine multiple comparison operations using logical operators. For example, to check if a number is within a certain range, we can use the and operator

num = 15

is_in_range = (num > 10) and (num < 20)

print(is_in_range)TrueThis checks if num is greater than 10 and less than 20, returning True if both conditions are met. Of course, we can also use or to check if at least one condition is met or not to negate a condition.

Functions are reusable blocks of code that perform a specific task. They help organize code, improve readability, and allow for code reuse. In Python, you define a function using the def keyword, followed by the function name and parentheses containing any parameters. For example, here is a simple function that takes two arguments, performs a calculation, and returns the result

def function_name(arg1, arg2):

r3 = arg1 + arg2

return r3Note that the indentation (whitespace at the beginning of a line) is crucial in Python, as it defines the scope of the function. The code block inside the function must be indented consistently. In the example above, two spaces are used for indentation, but tabs or four spaces are also common conventions. VSCode will automatically convert tabs to spaces based on your settings and the convention used in the file.

Suppose we want to create a function that greets a user by their name. We can define such a function as follows

def greet(name):

greeting = f"Hello, {name}!"

return greetingYou can then call the function by passing the required argument

message = greet("Alba")

print(message)Hello, Alba!We could also define the function without a return value and simply print the greeting directly

def greet_print(name):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")You can call this function in the same way

greet_print("Alba")Hello, Alba!We can also define functions with multiple outputs by returning a tuple of values. For example, here is a function that takes two numbers and returns both their sum and product

def sum_and_product(x, y):

sum_result = x + y

product_result = x * y

return sum_result, product_resultYou can call this function and unpack the returned values into separate variables

s, p = sum_and_product(5, 10)

print(f"Sum: {s}, Product: {p}")Sum: 15, Product: 50or you can capture the returned tuple in a single variable

result = sum_and_product(5, 10)

print(f"Result: {result}")Result: (15, 50)You can define functions with multiple return statements to handle different conditions. For example, here is a function that checks if a number is positive, negative, or zero and returns an appropriate message

def check_number(num):

if num > 0:

return "Positive"

elif num < 0:

return "Negative"

else:

return "Zero"You can call this function with different numbers to see the results

print(check_number(10)) # Output: PositivePositiveprint(check_number(-5)) # Output: NegativeNegativeprint(check_number(0)) # Output: ZeroZeroWhen you pass a variable to a function, the function receives a local copy of that value. Modifying this copy inside the function does not affect the original variable outside. However, if you need to modify a variable defined outside the function (a global variable), you must explicitly declare it using the global keyword. The difference between local and global variables is also called the scope of a variable. The following example illustrates the difference

global_var = 10

def edit_input(input_var):

# Access the input variable

print("Input you gave me", input_var)

input_var = input_var + 5 # This modifies the local copy of input_var and not global_var

print("Inside the function - modified input_var:", input_var)

return input_var # Return the modified value

def edit_global(input_var):

global global_var # Make global_var accessible inside the function

# Access the input variable

print("Input you gave me", input_var)

global_var = global_var + input_var # This modifies the global variable

print("Inside the function - modified global_var:", global_var)

return None

# Call the function

edit_input(global_var)Input you gave me 10

Inside the function - modified input_var: 15

15print("Outside the function - global_var:", global_var) Outside the function - global_var: 10# Call the function

edit_global(global_var)Input you gave me 10

Inside the function - modified global_var: 20print("Outside the function - global_var:", global_var) Outside the function - global_var: 20Oftentimes it is better to avoid global variables if possible, as they can lead to code that is harder to understand and maintain. Instead, prefer passing variables as arguments to functions and returning results. For example, if you would like to modify the value of global_var, you could simply assign the returned value of the function to it

global_var = edit_input(global_var)Input you gave me 20

Inside the function - modified input_var: 25print("Outside the function - global_var:", global_var) Outside the function - global_var: 25Functions can also have default arguments, which are used if no value is provided when the function is called. For example, here is a function that greets a user with a default name if none is provided

def greet_with_default(name="Guest"):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

greet_with_default()Hello, Guest!greet_with_default("Jesus")Hello, Jesus!We used the same function, once without providing an argument (so it uses the default value “Guest”) and once with a specific name (“Jesus”).

We can also use keyword arguments to call functions. This allows us to specify the names of the parameters when calling the function, making it clear what each argument represents. For example

def introduce(name, age):

print(f"My name is {name} and I am {age} years old.")

introduce(name="Alba", age=30)My name is Alba and I am 30 years old.We can even change the order of the arguments when using keyword arguments, as shown above. You can also mix positional and keyword arguments, but positional arguments must come before keyword arguments.

introduce("Alba", age=30) # This worksMy name is Alba and I am 30 years old.#introduce(age=30, "Alba") # This will raise a SyntaxErrorPositional arguments must be provided in the correct order, starting from the first parameter defined in the function. If you try to provide them in the wrong order, Python will raise a TypeError. For example, the following code will raise an error because the first argument is expected to be name, but we intended to provide an integer for age.

#introduce(30, name="Alba") # This will raise a TypeErrorFinally, note that the function needs to be defined before it is called in the code. If you try to call a function before its definition, Python will raise a NameError indicating that the function is not defined.

#test_function() # This will raise a NameError

def test_function():

print("This is a test function.")But the following will work correctly

def test_function():

print("This is a test function.")

test_function() # This will work correctlyThis is a test function.For this reason, function definitions are often placed at the beginning of a script or notebook cell, before any calls to those functions.

Conditional statements allow you to control the flow of your program based on certain conditions. In Python, you can use if, elif, and else statements to execute different blocks of code depending on whether a condition is true or false. We have already seen an example of this in the check_number function above.

In the following example, the do_something() function will only be executed if condition evaluates to True, while do_some_other_thing() will always be executed.

if condition:

do_something()

do_some_other_thing()It is important to note that Python uses indentation to define the scope of code blocks. The code inside the if statement must be indented consistently to indicate that it belongs to that block.

a = 10

if a > 5:

print("a is greater than 5")

print("This line is also part of the if block")a is greater than 5

This line is also part of the if blockprint("This line is outside the if block")This line is outside the if blockYou can also nest if statements within each other to create more complex conditions. For example

a = 10

if a > 5:

if a < 15:

print("a is between 5 and 15")

else:

print("a is greater than or equal to 15")

else:

print("a is less than or equal to 5")a is between 5 and 15Here, we first check if a is greater than 5. If that condition is true, we then check if a is less than 15. Depending on the outcome of these checks, different messages will be printed. Compared to the previous example, we also used an else statement to handle the case where a is not less than 15.

We can also use elif (short for “else if”) to check multiple conditions in a more concise way. For example

a = 10

if a < 5:

print("a is less than 5")

elif a < 15:

print("a is between 5 and 15")

else:

print("a is greater than or equal to 15")a is between 5 and 15To reach the elif block, the first if condition must evaluate to False. If it evaluates to True, the code inside that block will be executed, and the rest of the conditions will be skipped. If none of the conditions are met, the code inside the else block will be executed.

Note that if statements can also be written in a single line using a ternary conditional operator. For example

a = 10

result = "a is greater than 5" if a > 5 else "a is less than or equal to 5"

print(result)a is greater than 5The above code assigns a different string to the variable result based on the condition a > 5. If the condition is true, it assigns “a is greater than 5”; otherwise, it assigns “a is less than or equal to 5”.

Loops allow you to execute a block of code multiple times, which is useful for iterating over collections of data or performing repetitive tasks. In Python, there are two main types of loops: for loops and while loops.

while loops repeatedly execute a block of code as long as a specified condition is true. For example

count = 0

while count < 5:

print("Count is", count)

count += 1 # Increment count by 1Count is 0

Count is 1

Count is 2

Count is 3

Count is 4print("Final count is", count)Final count is 5In this example, the loop will continue to run as long as count is less than 5. Inside the loop, we print the current value of count and then increment it by 1. Once count reaches 5, the condition becomes false, and the loop exits. Note that count += 1 is a shorthand for count = count + 1.

for loops are used to iterate over a sequence (like a list, tuple, or string) or other iterable objects. We will see examples of such objects in the section on data structures. For the moment, let’s look at a simple example of a for loop that iterates over a list of numbers

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for num in numbers:

print("Number is", num)Number is 1

Number is 2

Number is 3

Number is 4

Number is 5or alternatively, we can use the range() function to generate a sequence of numbers to iterate over

for i in range(5): # Generates numbers from 0 to 4

print("i is:", i)i is: 0

i is: 1

i is: 2

i is: 3

i is: 4We can use the function range also to get a sequence of number to loop over. It follows the syntax range(start, stop, step)

start)stop-step)start + step, start + 2*step, start + 3*step, …for i in range(2, 10, 2): # Generates even numbers from 2 to 8

print("i is", i)i is 2

i is 4

i is 6

i is 8But as mentioned before, for loops can iterate over any iterable object, not just sequences of numbers. For example, we can iterate over the characters in a string

for letter in "Cemfi":

print(letter)C

e

m

f

ior over a list of strings

months_of_year = ["January", "February", "March", "April", "May", "June", "July", "August", "September", "October", "November", "December"]

# Loop through the months and add some summer vibes

for month in months_of_year:

if month == "June":

print(f"Get ready to enjoy the summer break, it's {month}!")

elif month == "July" or month =="August":

print(f"{month} is perfect to find reasons to escape from Madrid")

else:

print(f"Winter is coming")Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Get ready to enjoy the summer break, it's June!

July is perfect to find reasons to escape from Madrid

August is perfect to find reasons to escape from Madrid

Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Winter is coming

Winter is comingWhere we combined loops with conditional statements to print different messages based on the current month.

Note that you can use the break statement to exit a loop prematurely when a certain condition is met, and the continue statement to skip the current iteration and move to the next one.

for i in range(10):

if i == 5:

break # Exit the loop when i is 5

print("i is", i)i is 0

i is 1

i is 2

i is 3

i is 4for i in range(10):

if i % 2 == 0:

continue # Skip even numbers

print("i is", i)i is 1

i is 3

i is 5

i is 7

i is 9You can also create nested loops, where one loop is placed inside another loop. This is useful for iterating over multi-dimensional data structures or performing more complex tasks.

for i in range(3):

for j in range(2):

print(f"i: {i}, j: {j}")i: 0, j: 0

i: 0, j: 1

i: 1, j: 0

i: 1, j: 1

i: 2, j: 0

i: 2, j: 1enumerate() is a built-in function that adds a counter to an iterable and returns it as an enumerate object. This is particularly useful when you need both the index and the value of items in a loop.

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

for index, fruit in enumerate(fruits):

print(f"Index: {index}, Fruit: {fruit}")Index: 0, Fruit: apple

Index: 1, Fruit: banana

Index: 2, Fruit: cherryNow that we have covered the basics of Python programming, it’s time to practice what we’ve learned. Here are some exercises to help you reinforce your understanding of variables, data types, functions, conditionals, and loops.

a and b, and assign them the values 10 and 20, respectively. Write a function that takes these two variables as input and returns their product and their difference.is_even that takes a number as input and returns True if the number is even and False otherwise. Try calling the function with different numbers to test it.1 and 20. Print the final result. Hint: You could reuse the is_even function you defined earlier.1 and 1000 that are divisible by 3 or 5. Print the final result.The fundamental data types we have seen so far are useful for storing single values. However, in practice, we often need to work with collections of data. Python provides several built-in collection types to handle such cases. The most commonly used data structures in Python are

We will explore each of these types in more detail below.

We have already seen lists in some of the previous examples. A list is an ordered collection of items that can be of different types. Lists are mutable, meaning you can change their contents after creation. You can create a list by enclosing items in square brackets [], separated by commas.

my_list = [1, 2.5, "Hello", True]

print(my_list)[1, 2.5, 'Hello', True]We can access individual elements in a list using their index, which starts at 0 for the first element. For example

first_element = my_list[0]

print("First element:", first_element)First element: 1You can also access elements from the end of the list using negative indices, where -1 refers to the last element, -2 to the second last, and so on.

last_element = my_list[-1]

print("Last element:", last_element)Last element: TrueMultiple elements can be accessed using slicing, which allows you to specify a range of indices. The syntax for slicing is list[start:stop], where start is the index of the first element to include, and stop is the index of the first element to exclude.

sub_list = my_list[1:3] # Elements at index 1 and 2

print("Sub-list:", sub_list)Sub-list: [2.5, 'Hello']Since lists are mutable, you can modify their contents. For example, you can change the value of an element at a specific index.

my_list[2] = "World"

print("After modification:", my_list)After modification: [1, 2.5, 'World', True]To add elements to a list, we can use the append() method to add an item to the end of the list or the insert() method to add an item at a specific index, or extend() to add multiple items at once.

my_list.append("New Item")

print("After appending:", my_list)After appending: [1, 2.5, 'World', True, 'New Item']my_list.insert(1, "Inserted Item")

print("After inserting:", my_list)After inserting: [1, 'Inserted Item', 2.5, 'World', True, 'New Item']my_list.extend([3, 4, 5])

print("After extending:", my_list)After extending: [1, 'Inserted Item', 2.5, 'World', True, 'New Item', 3, 4, 5]Note how these methods modify the original list in place and return None, so you should not write my_list = my_list.append(...).

There are also options to remove items from a list. You can use the remove() method to remove the first occurrence of a specific value, the pop() method to remove an item at a specific index (or the last item if no index is provided), or the clear() method to remove all items from the list.

my_list.remove("World")

print("After removing 'World':", my_list)After removing 'World': [1, 'Inserted Item', 2.5, True, 'New Item', 3, 4, 5]popped_item = my_list.pop(2) # Remove item at index 2

print("After popping index 2:", my_list)After popping index 2: [1, 'Inserted Item', True, 'New Item', 3, 4, 5]print("Popped item:", popped_item)Popped item: 2.5my_list.clear()

print("After clearing:", my_list)After clearing: []There is a convenient way to create lists using list comprehensions. List comprehensions provide a concise way to create lists based on existing iterables. The syntax is [expression for item in iterable if condition], where expression is the value to be added to the list, item is the variable representing each element in the iterable, and condition is an optional filter. For example, here is how to create a list of squares of even numbers from 0 to 9.

squares_of_even = [x**2 for x in range(10) if x % 2 == 0]

print("Squares of even numbers:", squares_of_even)Squares of even numbers: [0, 4, 16, 36, 64]Let’s break down the list comprehension above:

x**2: This is the expression that defines what each element in the new list will be. In this case, it’s the square of x.for x in range(10): This part iterates over the numbers from 0 to 9.if x % 2 == 0: This is a condition that filters the numbers, including only even numbers in the new list. It uses the modulus operator % to check if x is divisible by 2. If a number is divisible by 2, the remainder is 0, indicating that it is even.Tuples are similar to lists in that they are ordered collections of items. However, tuples are immutable, meaning that once they are created, their contents cannot be changed. You can create a tuple by enclosing items in parentheses (), separated by commas.

my_tuple = (1, 2.5, "Hello", True)

print(my_tuple)(1, 2.5, 'Hello', True)You can access elements in a tuple using indexing and slicing, just like with lists.

first_element = my_tuple[0]

print("First element:", first_element)First element: 1second_element = my_tuple[1]

print("Second element:", second_element)Second element: 2.5last_element = my_tuple[-1]

print("Last element:", last_element)Last element: Truesub_tuple = my_tuple[1:3] # Elements at index 1 and 2

print("Sub-tuple:", sub_tuple)Sub-tuple: (2.5, 'Hello')Note that we have seen tuples before when we defined functions that return multiple values. In such cases, Python automatically packs the returned values into a tuple, which can then be unpacked into separate variables.

def get_coordinates():

x = 10

y = 20

return x, y # Returns a tuple (10, 20)

x_coord, y_coord = get_coordinates() # Unpacks the tuple into separate variables

print("X coordinate:", x_coord)X coordinate: 10print("Y coordinate:", y_coord)Y coordinate: 20Note that tuples are faster than lists for certain operations due to their immutability, making them a good choice for storing data that should not change. If you need to be able to modify the contents, use a list instead. For example, the following code will raise an error because we are trying to change an element of a tuple

#my_tuple[1] = 3.0 # This will raise a TypeErrorWhile tuples are immutable, you can concatenate two tuples to create a new tuple

tuple1 = (1, 2, 3)

tuple2 = (4, 5, 6)

combined_tuple = tuple1 + tuple2

print("Combined tuple:", combined_tuple)Combined tuple: (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)or you can repeat a tuple multiple times

repeated_tuple = tuple1 * 3

print("Repeated tuple:", repeated_tuple)Repeated tuple: (1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3)Unpacking can also be used with tuples. For example, you can unpack the elements of a tuple into separate variables

my_tuple = (10, 20, 30)

a, b, c = my_tuple

print("a:", a)a: 10print("b:", b)b: 20print("c:", c)c: 30If you don’t want to unpack all elements, you can use the asterisk (*) operator to capture the remaining elements in a list

my_tuple = (10, 20, 30, 40, 50)

a, b, *rest = my_tuple

print("a:", a)a: 10print("b:", b)b: 20print("rest:", rest)rest: [30, 40, 50]It is also common to use _ (underscore) as a variable name for values that you want to ignore during unpacking

my_tuple = (10, 20, 30)

a, _, c = my_tuple # Ignore the second element

print("a:", a)a: 10print("c:", c)c: 30Dictionaries are ordered (unordered prior to Python 3.7) collections of key-value pairs. Each key is unique and is used to access its corresponding value. Dictionaries are mutable, meaning you can change their contents after creation. The keys in a dictionary must be unique and immutable (e.g., strings, numbers, or tuples), while the values can be of any data type and can be duplicated. You can create a dictionary by enclosing key-value pairs in curly braces {}, with each key and value separated by a colon : and pairs separated by commas.

my_dict = {"name": "Alba", "age": 30, "is_student": False}

print(my_dict){'name': 'Alba', 'age': 30, 'is_student': False}You can access values in a dictionary using their keys. For example

name = my_dict["name"]

print("Name:", name)Name: AlbaYou can also add new key-value pairs or update existing ones

my_dict["city"] = "Madrid" # Add a new key-value pair

print("After adding city:", my_dict)After adding city: {'name': 'Alba', 'age': 30, 'is_student': False, 'city': 'Madrid'}Alternatively, you can use the update() method to add or update multiple key-value pairs at once

my_dict.update({"age": 31, "country": "Spain"})

print("After updating age and adding country:", my_dict)After updating age and adding country: {'name': 'Alba', 'age': 31, 'is_student': False, 'city': 'Madrid', 'country': 'Spain'}Note that if you use a key that already exists in the dictionary, the corresponding value will be updated. This applies whether you use the assignment syntax or the update() method.

The keys and values can be accessed using the keys() and values() methods, respectively. You can also use the items() method to get key-value pairs as tuples.

keys = my_dict.keys()

print("Keys:", keys)Keys: dict_keys(['name', 'age', 'is_student', 'city', 'country'])values = my_dict.values()

print("Values:", values)Values: dict_values(['Alba', 31, False, 'Madrid', 'Spain'])items = my_dict.items()

print("Items:", items)Items: dict_items([('name', 'Alba'), ('age', 31), ('is_student', False), ('city', 'Madrid'), ('country', 'Spain')])The latter is particularly useful for iterating over both keys and values in a loop.

We can remove key-value pairs from a dictionary using the del statement or the pop() method.

del my_dict["is_student"]

print("After deleting is_student:", my_dict)After deleting is_student: {'name': 'Alba', 'age': 31, 'city': 'Madrid', 'country': 'Spain'}age = my_dict.pop("age")

print("After popping age:", my_dict)After popping age: {'name': 'Alba', 'city': 'Madrid', 'country': 'Spain'}print("Popped age:", age)Popped age: 31Sets are unordered collections of unique items. They are mutable, meaning you can change their contents after creation. Sets are useful for storing items when the order does not matter and duplicates are not allowed. You can create a set by enclosing items in curly braces {}, separated by commas.

my_set = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

print("Set:", my_set)Set: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}You can also create a set from an iterable, such as a list, using the set() constructor.

my_list = [1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5]

my_set_from_list = set(my_list)

print("Set from list:", my_set_from_list)Set from list: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}You can add items to a set using the add() method and remove items using the remove() or discard() methods.

my_set.add(6)

print("After adding 6:", my_set)After adding 6: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}my_set.remove(3)

print("After removing 3:", my_set)After removing 3: {1, 2, 4, 5, 6}my_set.discard(10) # Does not raise an error if 10 is not in the set

print("After discarding 10:", my_set)After discarding 10: {1, 2, 4, 5, 6}There is also a frozenset type, which is an immutable version of a set. Once created, the contents of a frozenset cannot be changed. You can create a frozenset using the frozenset() constructor.

my_frozenset = frozenset([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

print("Frozenset:", my_frozenset)Frozenset: frozenset({1, 2, 3, 4, 5})Sets are particularly useful for performing mathematical set operations such as union, intersection, difference, and symmetric difference. For example

set_a = {1, 2, 3, 4}

set_b = {3, 4, 5, 6}

union_set = set_a.union(set_b)

print("Union:", union_set)Union: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}intersection_set = set_a.intersection(set_b)

print("Intersection:", intersection_set)Intersection: {3, 4}difference_set = set_a.difference(set_b)

print("Difference (A - B):", difference_set)Difference (A - B): {1, 2}symmetric_difference_set = set_a.symmetric_difference(set_b)

print("Symmetric Difference:", symmetric_difference_set)Symmetric Difference: {1, 2, 5, 6}More compactly, you can use operators for these operations

union_set = set_a | set_b

intersection_set = set_a & set_b

difference_set = set_a - set_b

symmetric_difference_set = set_a ^ set_bRanges are immutable sequences of numbers, commonly used for iteration in loops. You can create a range using the range() function, which generates a sequence of numbers based on the specified start, stop, and step values. The syntax is range(start, stop, step), where start is the first number in the sequence (inclusive), stop is the end of the sequence (exclusive), and step is the increment between each number.

my_range = range(0, 10, 2) # Generates numbers from 0 to 8 with a step of 2

print("Range:", list(my_range)) # Convert to list for displayRange: [0, 2, 4, 6, 8]You can also create a range with just the stop value, in which case the sequence starts from 0 and increments by 1 by default.

my_range_default = range(5) # Generates numbers from 0 to 4

print("Range with default start and step:", list(my_range_default))Range with default start and step: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]You have seen earlier how to use ranges in for loops to iterate over a sequence of numbers. Ranges are memory efficient because they generate numbers on-the-fly and do not store the entire sequence in memory, making them suitable for large sequences.

In the examples up to now you have already seen that data types can be classified as either mutable or immutable based on whether their values can be changed after they are created.

Mutable objects: These objects can be modified after they are created. Examples of mutable data types in Python include lists, dictionaries, and sets. When you modify a mutable object, you are changing the object itself, and any other references to that object will reflect the changes.

Immutable objects: These objects cannot be modified after they are created. Examples of immutable data types in Python include integers, floats, strings, and tuples. When you attempt to modify an immutable object, you are actually creating a new object with the modified value, leaving the original object unchanged.

An important implication of mutability is what happens when you assign one variable to another. For mutable objects, both variables will reference the same object in memory, so changes made through one variable will affect the other. For immutable objects, each variable will reference its own separate object.

# Mutable example with lists

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list2 = list1 # Both variables reference the same list

list2.append(4) # Modify list2

print("list1:", list1) # list1 is also affectedlist1: [1, 2, 3, 4]print("list2:", list2)list2: [1, 2, 3, 4]# Immutable example with strings

str1 = "Hello"

str2 = str1 # Both variables reference the same string

str2 += ", World!" # Modify str2 (creates a new string)

print("str1:", str1) # str1 remains unchangedstr1: Helloprint("str2:", str2)str2: Hello, World!The concept of mutability is important to understand when working with data structures and functions in Python, as it can affect how data is passed and modified within your code. When passing mutable objects to functions, changes made to the object within the function will affect the original object outside the function.

def modify_list(input_list):

input_list.append(100) # Modifies the original list

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

modify_list(my_list)

print(my_list) # my_list is changed[1, 2, 3, 100]In contrast, passing immutable objects to functions will not affect the original object.

def modify_int(input_int):

input_int += 10 # Creates a new integer

my_int = 5

modify_int(my_int)

print(my_int) # my_int remains unchanged5Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of the mutability of the data types you are working with to avoid unintended side effects in your code.

Now that we have covered the basics of data structures in Python, it’s time to practice what we’ve learned. Here are some exercises to help you reinforce your understanding of lists, tuples, dictionaries, sets, and ranges.

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm that organizes code around “objects” - which combine data (attributes) and functions (methods) that operate on that data. Think of objects as self-contained units that represent real-world entities or concepts. In Python, everything is an object, including basic data types like integers and strings. Therefore, we have been using OOP concepts all along without being explicit about it.

A class is like a blueprint or template for creating objects. An object is a specific instance created from that class. For example, if “Car” is a class, then “my_toyota” and “your_honda” would be objects (instances) of that class.

Here’s a simple example of defining a class and creating objects from it:

# Define a class

class BankAccount:

def __init__(self, owner, balance=0):

self.owner = owner

self.balance = balance

def deposit(self, amount):

self.balance += amount

print(f"Deposited ${amount}. New balance: ${self.balance}")

def withdraw(self, amount):

if amount > self.balance:

print("Insufficient funds!")

else:

self.balance -= amount

print(f"Withdrew ${amount}. New balance: ${self.balance}")

# Create objects (instances)

account1 = BankAccount("Alba", 1000)

account2 = BankAccount("Jesus", 500)

# Use methods

account1.deposit(200)Deposited $200. New balance: $1200account1.withdraw(300)Withdrew $300. New balance: $900# Check balances (accessing attributes)

print(f"{account1.owner}'s balance: ${account1.balance}")Alba's balance: $900print(f"{account2.owner}'s balance: ${account2.balance}")Jesus's balance: $500The __init__ method is a special method called a constructor that runs automatically when you create a new object. The self parameter refers to the instance itself and is used to access its attributes and methods.

Attributes are variables that belong to an object and store its data. Methods are functions that belong to an object and define its behavior.

class Student:

def __init__(self, name, student_id):

self.name = name # attribute

self.student_id = student_id # attribute

self.courses = [] # attribute

def enroll(self, course): # method

self.courses.append(course)

print(f"{self.name} enrolled in {course}")

def get_courses(self): # method

return self.courses

# Create and use a student object

student = Student("Alba", "S12345")

student.enroll("Artificial Intelligence and Big Data")Alba enrolled in Artificial Intelligence and Big Datastudent.enroll("Python Programming")Alba enrolled in Python Programmingprint(f"{student.name}'s courses: {student.get_courses()}")Alba's courses: ['Artificial Intelligence and Big Data', 'Python Programming']Inheritance is a fundamental OOP concept where a new class (called a child or subclass) can be based on an existing class (called a parent or superclass). The child class inherits all the attributes and methods of the parent class and can add new ones or modify existing behavior.

# Parent class

class Animal:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def speak(self):

print(f"{self.name} makes a sound")

def sleep(self):

print(f"{self.name} is sleeping... Zzz")

# Child class inherits from Animal

class Dog(Animal):

def __init__(self, name, breed):

super().__init__(name) # Call the parent's __init__

self.breed = breed # Add a new attribute

def speak(self): # Override the parent's method

print(f"{self.name} barks!")

def fetch(self): # Add a new method

print(f"{self.name} fetches the ball")

# Create objects

generic_animal = Animal("Generic")

my_dog = Dog("Buddy", "Labrador")

# Method inheritance: Dog inherits sleep() from Animal without modification

my_dog.sleep()Buddy is sleeping... Zzz# Method overriding: Dog has its own version of speak()

generic_animal.speak()Generic makes a soundmy_dog.speak()Buddy barks!# New method: fetch() is only available in Dog

my_dog.fetch()Buddy fetches the ballprint(f"{my_dog.name} is a {my_dog.breed}")Buddy is a LabradorThis example demonstrates three key aspects of inheritance:

Dog class automatically gets the sleep() method from Animal without any additional code. When we call my_dog.sleep(), it uses the parent’s implementation.Dog class defines its own speak() method, which replaces the parent’s version. When we call my_dog.speak(), it prints “barks!” instead of “makes a sound”.Dog class adds a new fetch() method that doesn’t exist in Animal.The super() function is used to call methods from the parent class. In the example above, super().__init__(name) calls the Animal class’s constructor to initialize the name attribute before adding the breed attribute specific to dogs.

While we won’t create complex inheritance hierarchies in this course, understanding this concept helps when working with libraries like scikit-learn. For example, when you use a model like LinearRegression, it inherits from base classes that provide common methods like fit(), predict(), and score(). This is why all scikit-learn models share a consistent interface—they all inherit from the same base classes.

# Preview: scikit-learn models use inheritance

# All estimators inherit common methods from base classes

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor

# Both models have the same interface because they inherit from the same base class

lr = LinearRegression()

dt = DecisionTreeRegressor()

# Both have fit(), predict(), score() methods inherited from base classes

print("LinearRegression methods:", [m for m in dir(lr) if not m.startswith('_')][:5])LinearRegression methods: ['copy_X', 'fit', 'fit_intercept', 'get_metadata_routing', 'get_params']print("DecisionTreeRegressor methods:", [m for m in dir(dt) if not m.startswith('_')][:5])DecisionTreeRegressor methods: ['apply', 'ccp_alpha', 'class_weight', 'cost_complexity_pruning_path', 'criterion']OOP helps organize complex programs by grouping related data and functionality together. This makes code:

In data science, you’ll often work with objects like DataFrames (from pandas), models (from scikit-learn), or plots (from matplotlib), even if you don’t create your own classes frequently.

# Example: You're already using OOP when working with lists!

my_list = [1, 2, 3] # my_list is an object of class 'list'

my_list.append(4) # append is a method

my_list.sort() # sort is a method

print(len(my_list)) # len works with the object's internal data4For this course, understanding how to use objects and their methods is more important than creating complex class hierarchies. Most of the time, you’ll be using classes created by others (like pandas DataFrames or scikit-learn models) rather than writing your own.

Now that we have covered the basics of object-oriented programming in Python, here are some exercises to help reinforce your understanding of classes, objects, attributes, methods, and inheritance.

Create a Rectangle class with width and height attributes. Add methods area() that returns the area and perimeter() that returns the perimeter. Create a rectangle object and test both methods.

Create a Counter class with a count attribute that starts at 0. Add methods increment() to increase the count by 1, decrement() to decrease it by 1, and reset() to set it back to 0. Test your class by creating a counter and calling its methods.

Create a Vehicle parent class with attributes brand and year, and a method info() that prints vehicle information. Then create a Car child class that adds a num_doors attribute and overrides the info() method to also display the number of doors.

In this section, we will introduce some of the most essential packages in Python for data science and scientific computing. These packages provide powerful tools and functionalities that make it easier to work with data, perform numerical computations, and create visualizations.

A module, in Python, is a program that can be imported into interactive mode or other programs for use. A Python package typically comprises multiple modules. Physically, a package is a directory containing modules and possibly subdirectories, each potentially containing further modules. Conceptually, a package links all modules together using the package name for reference.

NumPy (Numerical Python) is one of the most common packages used in Python. In fact, numerous computational packages that offer scientific capabilities utilize NumPy’s array objects as a standard interface for data exchange. That’s why understanding NumPy arrays and array-based computing principles is crucial.

NumPy offers a vast array of efficient methods for creating and manipulating numerical data arrays. Unlike Python lists, which can accommodate various data types within a single list, NumPy arrays require homogeneity among their elements for efficient mathematical operations. Utilizing NumPy arrays provides advantages such as faster execution and reduced memory consumption compared to Python lists. With NumPy, data storage is optimized through the specification of data types, enhancing code optimization.

Documentation for this package is available at https://numpy.org/doc/stable/.

To use NumPy in your code, you typically import it with the alias np

import numpy as npArrays serve as a fundamental data structure within the NumPy. They represent a grid of values containing information on raw data, element location, and interpretation. Elements share a common data type, known as the array dtype.

One method of initializing NumPy arrays involves using Python lists, with nested lists employed for two- or higher-dimensional data structures.

a = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6])

print("1D array:", a)1D array: [1 2 3 4 5 6]We can access the elements through indexing.

a[0]np.int64(1)Arrays are N-Dimensional (that’s why sometimes we refer to them as ndarray). That means that NumPy arrays will encompass vector (1-Dimensions), Matrices (2D) or tensors (3D and higher). We can get all the information of the array by checking its attributes. To create a 2D array, we can use nested lists:

a = np.array([[1, 2, 3, 4], [5, 6, 7, 8]])Mathematically, we can think of this as a matrix with 2 rows and 4 columns, i.e.,

\[a=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 \end{bmatrix}\]

We can check its attributes to get more information about the array:

print('Dimensions/axes:', a.ndim)Dimensions/axes: 2print('Shape (size of array in each dimension):', a.shape)Shape (size of array in each dimension): (2, 4)print('Size (total number of elements):', a.size)Size (total number of elements): 8print('Number of bytes:', a.nbytes)Number of bytes: 64print('Data type:', a.dtype)Data type: int64print('Item size (in bytes):', a.itemsize)Item size (in bytes): 8We have already seen how to access elements in a 1D array. For 2D arrays, we can use two indices: the first for the row and the second for the column.

element = a[0, 2] # Access the element in the first row and third column

print("Element at (0, 2):", element)Element at (0, 2): 3We can also use slicing to access subarrays. For example, to get the first two rows and the first three columns:

subarray = a[0:2, 0:3]

print("Subarray:\n", subarray)Subarray:

[[1 2 3]

[5 6 7]]We don’t need to specify both indices all the time. For example, to get the first row, we can do

first_row = a[0, :]

print("First row:", first_row)First row: [1 2 3 4]or to get the second column

second_column = a[:, 1]

print("Second column:", second_column)Second column: [2 6]We can initialize arrays using different commands depending on our aim. For instance, the most straightforward case would be to pass a list to np.array() to create one:

arr1 = np.array([5,6,7])

arr1array([5, 6, 7])However, sometimes we are more ambiguous and have no information on what our array contains. We just need to be able to initialize an array so that later on, our code, can update it. For this, we typically create arrays of the desired dimensions and fill them with zeros (np.zeros()), ones (np.ones()), with a given value (np.full()) or without initializing (np.empty()).

When working with large data, np.empty() can be faster and more efficient. Also, large arrays can take up most of your memory and, in those cases, carefully establishing the dtype() can help to manage memory more efficiently (i.e., choose 8 bits over 64 bits.)

np.zeros(4)array([0., 0., 0., 0.])np.ones((2,3))array([[1., 1., 1.],

[1., 1., 1.]])To create higher-dimensional arrays, we can pass a tuple representing the shape of the array:

np.ones((3,2,1))array([[[1.],

[1.]],

[[1.],

[1.]],

[[1.],

[1.]]])This created a 3D array with 3 layers of matrices with 2 rows and 1 column.

We can use np.full() to create an array of constant values that we specify in the fill_value option.

np.full((2,2) , fill_value= 4)array([[4, 4],

[4, 4]])np.empty() creates an array without initializing its values. The values in the array will be whatever is already present in the allocated memory, which can be random and unpredictable.

np.empty(2)array([0., 1.])With np.linspace(), we can create arrays with evenly spaced values over a specified range. The syntax is np.linspace(start, stop, num), where start is the starting value, stop is the ending value, and num is the number of evenly spaced values to generate.

np.linspace(0, 1, 5) # Generates 5 evenly spaced values between 0 and 1array([0. , 0.25, 0.5 , 0.75, 1. ])np.arange() is another useful function to create arrays with evenly spaced values, similar to the built-in range() function but returning a NumPy array. The syntax is np.arange(start, stop, step), where start is the starting value, stop is the ending value (exclusive), and step is the increment between each value.

np.arange(0, 10, 2) # Generates values from 0 to 8 with a step of 2array([0, 2, 4, 6, 8])Note that both np.linspace() and np.arange() can be used to create sequences of numbers, but they differ in how you specify the spacing and the number of elements. In general, use np.linspace() when you want a specific number of evenly spaced values over a range, and use np.arange() when you want to specify the step size between values.

Sometimes, you might also need to create identity matrices, which are square matrices with ones on the diagonal and zeros elsewhere. You can use np.eye() to create an identity matrix of a specified size.

np.eye(3) # Creates a 3x3 identity matrixarray([[1., 0., 0.],

[0., 1., 0.],

[0., 0., 1.]])Or you might want to create diagonal matrices with specific values on the diagonal. You can use np.diag() for this purpose.

np.diag([1, 2, 3]) # Creates a diagonal matrix with 1, 2, 3 on the diagonalarray([[1, 0, 0],

[0, 2, 0],

[0, 0, 3]])Finally, to create random arrays, NumPy provides several functions in the np.random module. For example, you can create an array of random floats between 0 and 1 using np.random.rand(), or an array of random integers within a specified range using np.random.randint(), or a normal distribution using np.random.randn().

np.random.rand(2, 3) # Creates a 2x3 array of random floats between 0 and 1array([[0.51054167, 0.74712546, 0.84384734],

[0.44542501, 0.18696529, 0.19825912]])np.random.randint(0, 10, size=(2, 3)) # Creates a 2x3 array of random integers between 0 and 9array([[1, 9, 9],

[4, 8, 5]])np.random.randn(2, 3) # Creates a 2x3 array of random floats from a standard normal distributionarray([[ 0.96270181, -1.25295514, -1.70274061],

[ 0.58874748, -0.13762351, -0.85271603]])When generating random numbers, it’s often useful to set a random seed using np.random.seed(). This ensures that the sequence of random numbers generated is reproducible, meaning that you will get the same random numbers each time you run your code with the same seed. This is particularly important for debugging and sharing results.

Arrays accept common operations like sorting, concatenating and finding unique elements.

For instance, using the sort() method we can sort elements within an array.

arr1 = np.array((10,2,5,3,50,0))

np.sort(arr1)array([ 0, 2, 3, 5, 10, 50])In multidimensional arrays, we can sort the elements of a given dimension by specifying the axis along which to sort. When axis=0, the operation collapses along the first dimension (rows in a 2D array), giving one result per column. When axis=1, it collapses along the second dimension (columns in a 2D array), giving one result per row.

mat1 = np.array([[1,2,3],[8,1,5]])

mat1array([[1, 2, 3],

[8, 1, 5]])mat1.sort(axis=1) # Sort along columns

mat1array([[1, 2, 3],

[1, 5, 8]])Using concatenate we can join the elements of two arrays along an existing axis.

arr1 = np.array((1,2,3))

arr2 = np.array((6,7,8))

np.concatenate((arr1,arr2))array([1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8])Instead, if we want to concatenate along a new axis, we use vstack() and hstack()

np.vstack((arr1,arr2)) # Vertical stackarray([[1, 2, 3],

[6, 7, 8]])np.hstack((arr1,arr2)) # Horizontal stackarray([1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8])It is also possible to reshape arrays. For instance, let’s reshape the concatenation of arr1 and arr2 to 3 rows and 2 columns

arr_c = np.concatenate((arr1,arr2))

arr_c.reshape((3,2))array([[1, 2],

[3, 6],

[7, 8]])We can also perform aggregation functions over all elements, like finding the minimum, maximum, means, sum of elements and much more.

print(arr1.min())1print(arr1.sum())6print(arr1.max())3print(arr1.mean())2.0This can also be done over a specific axis in multidimensional arrays. For example, let’s create a 2D array and find the sum across rows and columns

mat2 = np.array([[1,2,3],[4,5,6]])

print(mat2.sum(axis=0)) # Sum along rows[5 7 9]print(mat2.sum(axis=1)) # Sum along columns[ 6 15]It is also possible to get only the unique elements of an array or to count how many elements are repeated.

arr1 = np.array((1,2,3,3,1,1,5,6,7,8,11,11))

print(np.unique(arr1))[ 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 11]unq, count = np.unique(arr1, return_counts=True)

print("Unique elements:", unq)Unique elements: [ 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 11]print("Counts:", count)Counts: [3 1 2 1 1 1 1 2]Using where(), we can find the indices of elements that satisfy a given condition.

arr1 = np.array((10,15,20,25,30,35,40))

indices = np.where(arr1 > 25)

print("Indices of elements greater than 25:", indices)Indices of elements greater than 25: (array([4, 5, 6]),)We can also use boolean indexing to filter elements based on a condition.

filtered_elements = arr1[arr1 > 25]

print("Elements greater than 25:", filtered_elements)Elements greater than 25: [30 35 40]And we can replace elements that meet a condition using np.where()

new_arr = np.where(arr1 > 25, -1, arr1) # Replace elements greater than 25 with -1

print("Array after replacement:", new_arr)Array after replacement: [10 15 20 25 -1 -1 -1]NumPy arrays support common operations as addition, subtraction and multiplication. These operations are performed element-wise, meaning that they are applied to each corresponding element in the arrays.

A = np.array(((1,2,3),

(4,5,6)))

B = np.array(((10,20,30),

(40,50,60)))Element-wise addition, subtraction and multiplication can be performed with +, - and *.

A + Barray([[11, 22, 33],

[44, 55, 66]])B - Aarray([[ 9, 18, 27],

[36, 45, 54]])A * Barray([[ 10, 40, 90],

[160, 250, 360]])To multiply (*) or divide (/) all elements by an scalar, we just specify the scalar.

A * 10array([[10, 20, 30],

[40, 50, 60]])B / 10array([[1., 2., 3.],

[4., 5., 6.]])Note that NumPy automatically broadcasts the scalar to all elements of the array.

Broadcasting is a powerful mechanism in NumPy that allows operations to be performed on arrays of different shapes. When performing operations between arrays of different shapes, NumPy automatically expands the smaller array along the dimensions of the larger array so that they have compatible shapes. This process is called broadcasting.

For example, consider adding a 1D array to a 2D array. NumPy will “broadcast” the 1D array across the rows of the 2D array to perform the addition.

A = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6]])

B = np.array([10, 20, 30]) # 1D array

C = A + B # B is broadcasted across the rows of A

print(C)[[11 22 33]

[14 25 36]]Comparing NumPy arrays is also possible using operators as ==, !=, and the like. Comparisons will result in an array of booleans indicating if the condition is met for a given element.

arr1 = np.array(((1,2,3),(4,5,6)))

arr2 = np.array(((1,5,3),(7,2,6)))

arr1==arr2array([[ True, False, True],

[False, False, True]])Recall that we use double equals == for comparison, while a single equals = is used for assignment.

Note that element-wise multiplication is different from matrix multiplication. Matrix multiplication is achieved with either @ or matmul().

np.matmul(arr1,arr2.T) # Note the transpose of arr2 to match dimensionsarray([[20, 29],

[47, 74]])arr1 @ arr2.T # Note the transpose of arr2 to match dimensionsarray([[20, 29],

[47, 74]])a=np.array(['a','b','c','d','e','f','g']) and b = np.array(['g','h','c','a','e','w','g']). Find all elements that are equal. Can you get the position where the elements of both arrays match?Pandas is an open source library providing high-performance, easy-to-use data structures and data analysis tools. Pandas is particularly suited to the analysis of tabular data, i.e. data that can go into a table. In other words, if you can imagine the data in an Excel spreadsheet, then Pandas is the tool for the job.

Documentation for this package is available at https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/.

To use Pandas, you typically import it with the alias pd

import pandas as pdWe will also import NumPy as it is often used alongside Pandas for numerical operations.

import numpy as npPandas builds on two main data structures: Series and DataFrames. Series represent 1D arrays while DataFrames are 2D labeled arrays. The easiest way to think about both structures is to conceptualize DataFrames as containers of lower dimension data. That is, DataFrames columns are composed of Series, and each of the elements of a Series (i.e., the rows of the DataFrame) are individual scalar (numbers or strings) values. In plain words, Series are columns made of scalar elements and DataFrames are collections of Series that get an assigned label. All pandas data structures are value-mutable (i.e., we can change the values of elements and replace DataFrames) but some are not always size-mutable. The length of a Series cannot be changed, but, for example, columns can be inserted into a DataFrame.

A Series is a one-dimensional labeled array capable of holding any data type (integers, strings, floating point numbers, Python objects, etc.). The axis labels are collectively referred to as the index. A Series can be created from a list, dictionary, or scalar value using the pd.Series() constructor. To create a Series from a list, you can do the following:

data = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

series = pd.Series(data)If you want to specify custom index labels, you can pass a list of labels to the index parameter:

data = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

labels = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

series = pd.Series(data, index=labels)You can additionally assign a name to the Series using the name parameter:

data = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

labels = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

series = pd.Series(data, index=labels, name='My Series')These functions work the same way when creating a Series from a NumPy array. When creating a Series from a dictionary, the keys of the dictionary become the index labels, and the values become the data:

data = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30}

series = pd.Series(data)You can access elements in a Series using their index labels or integer positions. For example, to access the element with label ‘b’:

value = series['b']

print("Value at index 'b':", value)Value at index 'b': 20If you want to access elements by their integer position, you can use the iloc attribute:

value = series.iloc[1] # Access the second element (index 1)

print("Value at position 1:", value)Value at position 1: 20Note that both label-based and positional indexing can be used interchangeably in many cases.

.loc is used for label-based indexing, which means you access elements by their index labels:

| Syntax | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

series.loc[label] |

Single label access | s.loc['b'] |

Value at index ‘b’ |

series.loc[label_list] |

Multiple labels | s.loc[['a', 'c']] |

Series with values at ‘a’ and ‘c’ |

series.loc[start:end] |

Slice by labels (inclusive) | s.loc['a':'c'] |

Series from ‘a’ to ‘c’ (inclusive) |

series.loc[condition] |

Boolean indexing | s.loc[s > 5] |

Values where condition is True |

.iloc is used for positional indexing, which means you access elements by their integer position in the Series:

| Syntax | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

series.iloc[position] |

Single position access | s.iloc[1] |

Value at position 1 |

series.iloc[position_list] |

Multiple positions | s.iloc[[0, 2]] |

Series with values at positions 0 and 2 |

series.iloc[start:end] |

Slice by positions (exclusive end) | s.iloc[1:3] |

Series from position 1 to 2 |

series.iloc[negative_pos] |

Negative indexing | s.iloc[-1] |

Value at last position |

Key Differences:

.loc uses the actual index labels (strings, dates, etc.).iloc uses integer positions (0, 1, 2, …).loc slicing is inclusive of both endpoints.iloc slicing is exclusive of the end positionYou can retrieve all index labels and values of a Series using the index and values attributes, respectively:

index_labels = series.index

print("Index labels:", index_labels)Index labels: Index(['a', 'b', 'c'], dtype='object')values = series.values

print("Values:", values)Values: [10 20 30]You can perform various operations on Series, such as arithmetic operations, aggregation functions, and filtering. For example, to add a scalar value to all elements in the Series:

new_series = series + 5

print("Series after adding 5:\n", new_series)Series after adding 5:

a 15

b 25

c 35

dtype: int64You can also filter the Series based on a condition:

filtered_series = series[series > 20]

print("Filtered Series (values > 20):\n", filtered_series)Filtered Series (values > 20):

c 30

dtype: int64They work and behave similarly to NumPy arrays in many ways but with additional functionality for handling missing data and labeled data.

Pandas Series are great for one-dimensional data, but in data science, we often work with two-dimensional data tables. This is where Pandas DataFrames come into play. A DataFrame is a two-dimensional labeled data structure with columns of potentially different types. You can think of it as a spreadsheet or SQL table, or a dictionary of Series objects.

You can create a DataFrame from various data sources, such as dictionaries, lists of lists, or NumPy arrays. Here’s an example of creating a DataFrame from a dictionary:

data = {

'Name': ['Alba', 'Jesus', 'Yang'],

'Age': [30, 25, 35],

'City': ['New York', 'Los Angeles', 'Chicago']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

df = df.set_index('Name') # Set 'Name' as the index

print("DataFrame:\n", df)DataFrame:

Age City

Name

Alba 30 New York

Jesus 25 Los Angeles

Yang 35 ChicagoYou can also create a DataFrame from a list of lists:

# Creating a DataFrame from a list of lists

pd.DataFrame(

data=[

[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]

],

index=["R1", "R2", "R3"],

columns=["C1", "C2", "C3"]

) C1 C2 C3

R1 1 2 3

R2 4 5 6

R3 7 8 9There are several more ways to create DataFrames, including from CSV files, Excel files, SQL databases, and more. Most of the time, you’ll be loading data from external sources rather than creating DataFrames from scratch.

Indexing works similarly to Series, but now you have both row and column labels to consider. Here are some common ways to index and select data in a DataFrame:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

df[column_label] or df.column_label or df.loc[:, column_label] |

Access a single column by label (returns a Series) |

df[[col1, col2]] |

Access multiple columns by label (returns a DataFrame) |

df.loc[row_labels, column_labels] |

Access rows and columns by label (names) |

df.iloc[row_positions, column_positions] |

Access rows and columns by position (integers) |

df[boolean_condition] |

Filter rows based on a boolean condition |

Consider the following DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(

data={

"area": ["USA", "Eurozone", "Japan", "UK", "Canada", "Australia"],

"year": [2024, 2024, 2024, 2024, 2024, 2024],